By Chris Fielder

In March 2018, workers at the Rainforest Café in Niagara, Ontario, Canada voted overwhelmingly to unionize. The 77-person bargaining unit chose Workers United as their exclusive bargaining representative by a vote of 44 to 7. Almost a year later, the workers still lack a contract with the owners of the Niagara Rainforest Café, Canadian Niagara Hotels. They have been on strike since April 6th fighting against wage theft, union-busting, and sexual harassment.

Even without a first contract, a union election victory is remarkable for Rainforest Café workers. Though Workers United represents other hospitality workers across Canada, food and beverage retail remains a notoriously difficult industry to unionize. High turnover in the industry makes workers, many of whom live paycheck to paycheck, replaceable. The organizing climate for food and beverage workers is even more grim in the United States, where union density in restaurants and bars was, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics in 2018, below two percent.

Yet, the labor movement has made inroads in the industry over the past two years. Last year, Gimme! Coffee workers in Ithaca, N.Y. became the first baristas union in the United States. Earlier this year, Anchor Brewing workers, makers of the cult classic beer Anchor Steam, became the first craft brewery in the country to organize. With these breakthroughs, organizers attempting to penetrate the food and beverage retail industry should take notice of Workers United’s international mobilization strategies. The union has been an effective hammer when Canadian Niagara Hotels interfered with workers. The model might work industry-wide.

The Case

The minimum wage increased in Canada from $11.60 an hour to $14.00 in January 2018. In response, management increased the amount it took from employee tips twice; now, Rainforest Café seizes 4.5% of all employee tips. It also preys upon unaware consumers through a “voluntary” tourist tax printed on the bottom of each receipt and added to the bill. Workers voted in Workers United in March 2018, but a year after the union election, Rainforest Café workers and Canadian Niagara Hotels had not reached a contract. Workers were getting frustrated.

They were on the fence about striking until an employee sexually harassed and assaulted three female employees. Management did not fire the abuser, telling victims he was sorry and “couldn’t sleep at night”. One co-worker complained to his bosses about how the abuse had been handled; he was essentially told the decision was final. Strike fervor increased following the abuse, and workers voted to strike on April 6.

Canadian Niagara Hotels did not backpedal immediately, either. The abuser was not fired until five days after the strike began. The mother of one of the victims even went to dine at Rainforest Café after the strike had started; she received a letter in the mail a week later banning her from all Canadian Niagara Hotels properties for life. But, after three weeks of striking, workers grew discouraged and strapped for cash. Strike pay was at roughly $150 a week. Workers would have to find other jobs or go back into Rainforest Café to make ends meet.

A major boon to the Rainforest Café campaign is its relationship with Workers United in upstate New York and across the country. A transfer of willing picketers between the Rochester Regional Joint Board and the Canada Council gives boycotting more strength. Further, when the Workers United president heard about the degree to which strikers were suffering from low strike pay, she reached out to other Workers United locals. They were able to raise $25,000 in a matter of hours and increase strike pay to almost $500 a week. Even now, volunteers from Rochester picket regularly with Rainforest Café workers across the Canadian border. Though the strike is ongoing, more bodies means more leverage to hurt ownership’s bottom line. Longevity of strike leverage might be the workers’ greatest union asset in their fight.

Power Resources

Canadian Niagara Hotels owns multiple restaurants in Niagara Falls on the same block. To truly damage the owner’s income stream from their behavior during the strike, the union would have to launch a boycott of all its businesses. One advantage Rainforest Café strikers held was sheer numbers in their bargaining unit and via activists from the United States and Canada. When I visited the Rainforest Café picket line, it was a cold, wet, windy day. Even though we were all drenched and freezing, ten strikers still showed up. They routinely turn out 30-plus to their Saturday rallies. With enough strikers to surround the property, the workers are actually equipped to damage profits. The restaurant has been almost completely empty on some weekend rush times, and organizers estimate Rainforest Café had lost over $1.5 million by week 4 of the strike.

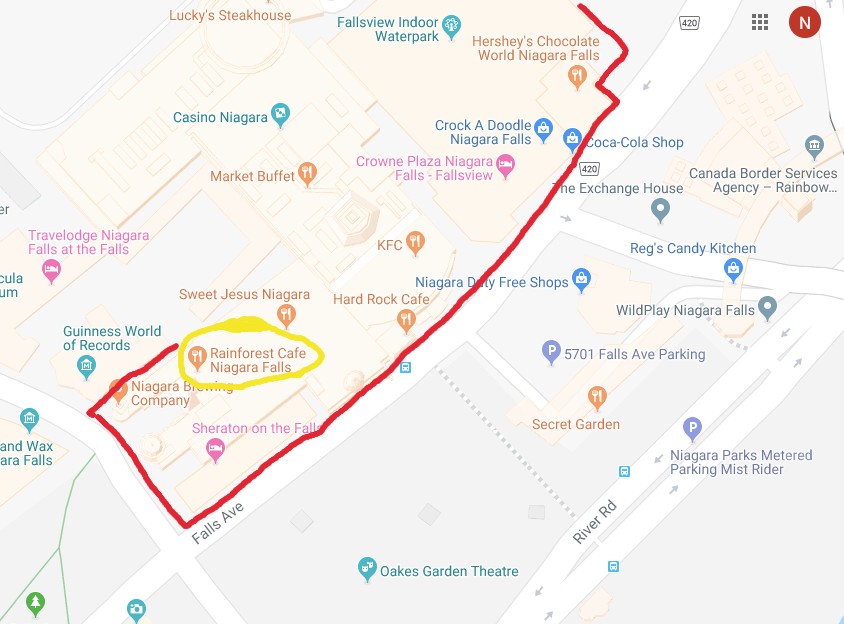

Canadian Niagara Hotels also owns the Niagara Brewing Company location to Rainforest Café’s left and property extending all around the block, including Sheraton Hotel, Crown Plaza Hotel, Casino Niagara, Hard Rock Café, an indoor waterpark, and Hershey’s. The map is detailed below:

There are also two paths into Rainforest Café facing the street, with a divider in between. To ward off customers, strikers occupied areas in front of each. Other strikers would stand in front of tourist sites (Hard Rock Café, Hershey’s), commonly frequented businesses (Starbucks inside Crown Plaza), and hotel entrances around the block on Falls Avenue. The owner’s control of the whole block initially presented a challenge. Strikers wanted to stay together in front of Rainforest Café, which only increased traffic at other businesses. As the strike grew more disciplined, however, organizers cut into the profits of multiple businesses and immediately got Canadian Niagara’s attention.

The partnership between the Rochester Regional Joint Board and Canada Council inflates associational power beyond the capabilities of conventional unions. It emulates the societal power of the Fight for $15 and Poor People’s Campaign with the hammer of associational alliances. Organizers admit that border proximity might make the Rainforest Café strike unique as opposed to other transnational union efforts. Yet, the ability to raise money quickly for Rainforest Café strikers suggests meaningful strength from Workers United to move into industries other unions deemed too challenging to organize. The boycott seeks to build broad societal power, and has succeeded in both public relations and practice. One father-daughter pair visiting Niagara Falls from Europe joined the picket line; Canadian Niagara Hotels kicked them out of their hotel room as a result. What followed was a CBC story, a scandal, and more associational energy among strikers. The transnational partnerships in this campaign have helped to create unforced errors from ownership.

Lessons Learned

In an industry whose workers so lack structural power, Workers United adds power elsewhere. Other food and beverage organizers should observe the following:

- Food and beverage workplaces have high turnover, but employees generally change jobs within the same geographic area.

- Structural power is the last step. Unions must win worker buy-in of strong associational power.

- The working-class lives in the food and beverage retail industry. Organizing even one restaurant must be a union-wide effort. The second restaurant organized in the same labor market will be easier once associational power is established.

- Do not discount latent societal power, nor the power of narratives to activate it. Customers are often willing to eat or drink somewhere else if workers and organizers are present to tell the story.

- Food and beverage retail workers lack structural power because unions are not willing to attack the industry. Are we fighting for the working class or not?